“I hate feeling this way.” She said, “…it is like I am wired to feel like this.”

I have heard variations of this sentiment many, many times. (Each time I am reminded, Yes! Yes you are wired to feel like this.) We as mammals ARE wired to feel like this, but that doesn’t mean it is never ending, that there is no hope. I then explain the process that occurs deep in our brain and she expresses a sense of relief. “THAT makes sense!” she exclaims. Understanding the underlying neurobiology to our processes helps us not just understand but regulate our nervous systems and those of our clients. Dan Siegel’s Interpersonal Neurobiology uses this principal as the basis for conceptualization and treatment (Badenbock, 2008)

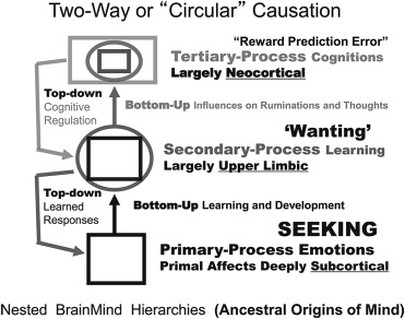

According to Jaak Panksepp, PhD, ALL mammals have seven primary affective (emotional) neurocircuits deep in the brain. They are adaptive, essential to our survival, and part of our basic brain structure. (Panksepp, 2014) While it is relatively well known now that the emotional center of the brain is in the limbic system, what Panksepp has found is that emotions are much more primitive, and hence much more powerful. The emotional pathways extend far beyond the limbic system into the upper and middle brain stem. (Panksepp, personal communication, 2014) These circuits reside in “ancient parts of the brain;” they are unconscious, hence the term primary. (Panksepp, 2014; Panksepp, 2012; Panksepp, 2010a) “All aspects of mental life can be influenced by our primary-process feelings and the overall affective spectrum of the lower MindBrain is foundational for higher mental health issues” (Panksepp, 2012, p. xii). Emotions do not originate by a cognitive process. They begin in basic biological experiences deep in our brains and the subtleties (determining if we are feeling shame or guilt, anxiety or excitement) are then determined by our life experiences and our interpretations (secondary and tertiary processes, respectively, which I will explain below). The term MindBrain or BrainMind is Panksepp’s acknowledgment that we can not separate mind from brain and body. His theory is controversial in the field of affective neurobiology, but his decades of research supports his proposals. This model will make sense to those who feel their emotions take over and to those therapists working with trauma and addiction. It also helps to explain the power of sex addiction and other process addictions.

First a few words of caution. This is a very basic overview. The labels Panksepp chose for these seven circuits are not necessarily what we think of when we hear the word he uses for the circuit (RAGE for example). He is not talking about the act of rage, but the neurological circuit in the brain that is the basis of the feeling (in this example anger and its associated behaviors). Getting past the labels of the circuits may take some time, that is okay. Because these systems are evolutionary and found in ALL mammals, he uses capital letters. Also, this helps distinguish them from our experience of an emotion, our first thought when we hear the word rage. The emotion in parentheses is the feeling equivalent that we experience so that there is a personal context for the neuronal structures in the brain. I will capitalize as well when referring to the primary process structures, rather than the feelings as we know them. Finally, the interpretation of how these systems play out in sex addiction are my conjectures and are not proven by his research. They are possibilities given my experience working with people and my understanding of his work. So what are these seven primary-process feelings?

FEAR (anxiety): There are two anxiety networks in the brain. One is FEAR; it is the flight system. It is there when we feel threatened and helps us stay out of danger. It is the one activated when we worry.

PANIC/GRIEF (sadness): PANIC is the other anxiety network in the brain; it is imperative to attachment. PANIC is separation anxiety or grief over the loss of a loved one. All mammals need an adult to survive when born, and the PANIC circuit is what helps infants attach to their parents. “Animals who are often separated from their mothers for extended periods of time become maladjusted” (Weintraub, 2012) Opioids are a significant part of the attachment and PANIC system in mammals, along with oxytocin and prolactin. Anyone addicted to opioids understands the power of the bond with this drug.

RAGE (anger): RAGE is the fight circuit. When backed into a corner an animal attacks, RAGE tells us we have to fight to survive. RAGE indicates that a boundary has been violated. Although uncomfortable, without anger there would be no civil rights movement, no defending of ourselves when attacked or when our loved ones are threatened. There are two types of anger, the first is agitated rage, which is uncomfortable and is the rage/anger most of us think of when we think of anger. This agitated rage is based in the RAGE circuit. The second is related to the SEEKING circuit.

SEEKING (expectancy): SEEKING is our curiosity, our need for newness. What is called the reward system is a part of this expansive, perhaps primary system. It is the largest affective circuit in the brain. In fact the term reward system is misleading, “as the brain has many reward systems” (Panksepp, 2014, Personal communication). This is what helps our brains develop new neurons (yes our brains do develop new neurons and new neuronal connections). According to Panksepp SEEKING is the basis of addiction (we all know the term drug seeking). What psychology calls the reward system is a small part of the SEEKING network. The reward system is, in part, Medial Forebrain Bundle, but it is so much more than just reward (Panksepp, 2014). It is curiosity and enthusiasm. It impacts anger. Interestingly, there are different types of anger, one is related to the SEEKING system which is predatory rage and is considered pleasurable. Rage associated with SEEKING may also be primary to sexualized rage, part of the rage associated with sexual addiction and sexual perpetrators (sex addicts are not necessarily sexual perpetrators). Animals with predatory rage try to increase it, while those with agitated rage try to decrease the experience. It seems that both RAGE and SEEKING circuits would be involved in sexualized rage and may be dependent upon the individual’s life experiences and genetics.

Panksepp argues that the description of “reward systems” in the brain disregards much of the processes and role of affect in our behavior. In fact deep brain stimulation of the Medial Forebrain Bundle (the reward system) create “states of positive enthusiasm, that normally accompany the appetitive-foraging phase of behavior in our species, as we have long predicted” (Panksepp, 2014, p. 210). This suggests that much more is happening than a simple behavioral view of reward and punishment. It adds a level of understanding to why the rewards are so powerful. If it were as simple as the behaviorists suggest, quitting an addiction would be easy via extinction and other behavioral interventions. Unfortunately addiction are not so easy to stop. It is not simply pleasure but an enjoyable feeling state that is directly related to our survival instincts.

However, he recognizes secondary and tertiary emotional processes that work in a circuit (see chart). Secondary processes are learning processes that arise from various forms of conditioning (rewards and punishments); while the tertiary process is our thinking and ruminating and what is commonly associated with emotional life and that is impacted by interventions such as Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. Tertiary processes are the worrying over and over what will happen if, the catastrophizing in anxiety, and the thoughts about how one will get a fix in addiction (Panksepp, 2010a).

In Archeology of Mind (2012), Panksepp writes, “Most modern psychoanalytic and cognitive-behavioral approaches to therapy fail to see SEEKING as a basic emotional urge. Some researchers also tend to confuse FEAR and PANIC/GRIEF, seeing anxiety as a single manifestation” (p.xv). I would add that therapist and doctors too see anxiety as a singular expression, when often the nuances are quite distinct. It is important to determine the difference as interventions may be more or less effective depending on the system involved. For example, when PANIC is involved I often need other strategies than cognitive interventions. Since SEEKING is such an important factor in addiction, more will be written about this and other systems in later posts.

CARE (nurturance): CARE is as it sounds, it is our affection for those close to us and for the world around us. It is our need to feel cared for and to care for others. It too is primary to our bonding with those we love.

LUST (sexual excitement): LUST is also part of our love for others and our need for sexual intimacy. In terms of survival we must have sex to propagate the species. Clearly in sexual compulsivity LUST is a primary process, however, it may not be the first activated for many individual but become active after the FEAR or PANIC or another system is involved.

PLAY (social joy): PLAY is integral to our emotional life, all animals play. It is the basis of joy in the brain. PLAY is imperative to brain development and attachment. Research has shown that playing enhances frontal lobe development. Play therapists know that getting on the floor and playing with one’s child improves attachment, this is why. As adults we must continue to have social engagement and playfulness. This is often a difficult task for recovering addicts, in part because play seems confused by SEEKING (excitement) and fun becomes the use of the drug or behavior. In other words the excitement of fix feels like fun, although it is another brain circuit altogether. This is where our secondary and tertiary processes come into the mix. PLAY stems from brain areas that are more basic - not higher order thinking. This is in part why Panksepp believes the removal of play from schools has led to a spike in ADHD. Finally, play reduces aggression, suggesting the link between these systems.

As you can see these networks interrelate. There is a saying in neuroscience, what fires together, wires together. This means that neurons that fire at the same time become paired together. This is a completely unconscious process. You can see how this plays out in various forms of addiction. SEEKING if activated with LUST leads to sexual searching. If our PANIC circuit is triggered and was alleviated by the enjoyment of LUST (sex), and this happens frequently the two networks in the brain will then fire off simultaneously when even one is activated. Additionally, if CARE and LUST become paired, for example through sexual abuse or other secondary and tertiary processes, then sex and intimacy become confused in a basic, unconscious way. I asked Dr. Panksepp if this is possible and he explained yes it was, in this manner:

"The SEEKING System is truly enormous, and beside integrating appetitive eagerness (enthusiasm), it also can be devoted to LUST issues where gonadal hormone receptors are concentrated (POA), as well as CARE where oxytocin and prolactin receptors are concentrated. Thus, all the positive emotional system, including PLAY converge on the SEEKING urge, but are distinct enough to be seen as distinguishable appetitive urges" (personal communication, 2014).

When secondary process of rewards and punishments come into play and then our interpretation of events and what this means about who we are, patterns of coping become quite complex. Given this complexity, changing behavior becomes very difficult. Anyone who is in recovery from sexual compulsion can attest to the difficulty of staying on the path.

This is not to say that all is lost and that adults are not responsible for their behavior. They most certainly are, but what this suggests is that we have to be aware of and work with the primary circuits for change to occur. Those working with addictions know this and do this inherently. Programs try to develop healthy fun activities to reengage the PLAY circuit with new behaviors. They are trying to disconnect PLAY from SEEKING, specifically drug seeking, and build the important social connection all of us need. SEEKING then changes too. In essence part of the work is pairing PLAY with CARE. However, addictions can be cunning, powerful, and baffling- a trigger can arise at any time. The primacy of these circuits gives us an understanding of why.

Finally, what most people call positive feelings, “indicate that animals are returning to “comfort zones” that support survival, while negative affects reflect “discomfort zones” that indicate that animals are in situations that may impair survival” (Panksepp, 2010a; Panksepp 2010b). Despite Panksepp’s word choice, this model suggests, and as Linehan and many others explicitly point out, that emotions are not good or bad, negative or positive, but they are either what Katie O’Shea describes as life protecting (FEAR, RAGE, PANIC) or life enhancing, helping us regulate our nervous systems by calming us and returning us to homeostasis (SEEKING, CARE, etc) (2014, training). Thinking about your feelings in this way can helps you accept your emotional experiences, become mindful of the process, and therefore less reactive to a feeling. Judging your feelings as bad only leads to resistance and a desire for the unpleasantness to go away and fear that the pleasant emotions won’t last. When faced with a difficult feeling, remind yourself that this is how your brain is designed to respond in order to protect you. Asking, “What is this emotion trying to protect me from?” can help shift your perspective.

REFERENCES

Bradenbock, Being a Brain-Wise Therapist.

O’Shea, K. (2014). When There are No Words. Training.

Panksepp, J. (2014.) Integrating Bottom-up Internalist Views of Emotional Feelings with Top-down Externalist Views: Might Brain Affective Changes Constitute Reward and Punishment Effect within Animal Brains? Cortex; 59: 208-213.

Panksepp, J. October 27, 2014. Email communication

Panksepp, J. (2012). Archeology of Mind. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Panksepp, J. (2010a) Affective neuroscience of the emotional BrainMind: Evolutionalry perspectives and implications for understanding depression. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience; 12(4): 533-545.

Panksepp, J. Archeology of Mind P.xii

Panksepp, J. (2010b). Dialogues Clinical Neuroscience. 12(4):533-545. Affective Neuroscience of the Emotional BrainMind: Evolutionary Perspectives and Implications for Understainding Depression.

Weintraub, P. (2012, May 31) Discover Interview: Jaak Panksepp Pinned Down Humanity’s 7 Primal Emotions. Discover Magazine. http://discovermagazine.com/2012/may/11-jaak-panksepp-rat-tickler-found-humans-7-primal-emotions.

I have heard variations of this sentiment many, many times. (Each time I am reminded, Yes! Yes you are wired to feel like this.) We as mammals ARE wired to feel like this, but that doesn’t mean it is never ending, that there is no hope. I then explain the process that occurs deep in our brain and she expresses a sense of relief. “THAT makes sense!” she exclaims. Understanding the underlying neurobiology to our processes helps us not just understand but regulate our nervous systems and those of our clients. Dan Siegel’s Interpersonal Neurobiology uses this principal as the basis for conceptualization and treatment (Badenbock, 2008)

According to Jaak Panksepp, PhD, ALL mammals have seven primary affective (emotional) neurocircuits deep in the brain. They are adaptive, essential to our survival, and part of our basic brain structure. (Panksepp, 2014) While it is relatively well known now that the emotional center of the brain is in the limbic system, what Panksepp has found is that emotions are much more primitive, and hence much more powerful. The emotional pathways extend far beyond the limbic system into the upper and middle brain stem. (Panksepp, personal communication, 2014) These circuits reside in “ancient parts of the brain;” they are unconscious, hence the term primary. (Panksepp, 2014; Panksepp, 2012; Panksepp, 2010a) “All aspects of mental life can be influenced by our primary-process feelings and the overall affective spectrum of the lower MindBrain is foundational for higher mental health issues” (Panksepp, 2012, p. xii). Emotions do not originate by a cognitive process. They begin in basic biological experiences deep in our brains and the subtleties (determining if we are feeling shame or guilt, anxiety or excitement) are then determined by our life experiences and our interpretations (secondary and tertiary processes, respectively, which I will explain below). The term MindBrain or BrainMind is Panksepp’s acknowledgment that we can not separate mind from brain and body. His theory is controversial in the field of affective neurobiology, but his decades of research supports his proposals. This model will make sense to those who feel their emotions take over and to those therapists working with trauma and addiction. It also helps to explain the power of sex addiction and other process addictions.

First a few words of caution. This is a very basic overview. The labels Panksepp chose for these seven circuits are not necessarily what we think of when we hear the word he uses for the circuit (RAGE for example). He is not talking about the act of rage, but the neurological circuit in the brain that is the basis of the feeling (in this example anger and its associated behaviors). Getting past the labels of the circuits may take some time, that is okay. Because these systems are evolutionary and found in ALL mammals, he uses capital letters. Also, this helps distinguish them from our experience of an emotion, our first thought when we hear the word rage. The emotion in parentheses is the feeling equivalent that we experience so that there is a personal context for the neuronal structures in the brain. I will capitalize as well when referring to the primary process structures, rather than the feelings as we know them. Finally, the interpretation of how these systems play out in sex addiction are my conjectures and are not proven by his research. They are possibilities given my experience working with people and my understanding of his work. So what are these seven primary-process feelings?

FEAR (anxiety): There are two anxiety networks in the brain. One is FEAR; it is the flight system. It is there when we feel threatened and helps us stay out of danger. It is the one activated when we worry.

PANIC/GRIEF (sadness): PANIC is the other anxiety network in the brain; it is imperative to attachment. PANIC is separation anxiety or grief over the loss of a loved one. All mammals need an adult to survive when born, and the PANIC circuit is what helps infants attach to their parents. “Animals who are often separated from their mothers for extended periods of time become maladjusted” (Weintraub, 2012) Opioids are a significant part of the attachment and PANIC system in mammals, along with oxytocin and prolactin. Anyone addicted to opioids understands the power of the bond with this drug.

RAGE (anger): RAGE is the fight circuit. When backed into a corner an animal attacks, RAGE tells us we have to fight to survive. RAGE indicates that a boundary has been violated. Although uncomfortable, without anger there would be no civil rights movement, no defending of ourselves when attacked or when our loved ones are threatened. There are two types of anger, the first is agitated rage, which is uncomfortable and is the rage/anger most of us think of when we think of anger. This agitated rage is based in the RAGE circuit. The second is related to the SEEKING circuit.

SEEKING (expectancy): SEEKING is our curiosity, our need for newness. What is called the reward system is a part of this expansive, perhaps primary system. It is the largest affective circuit in the brain. In fact the term reward system is misleading, “as the brain has many reward systems” (Panksepp, 2014, Personal communication). This is what helps our brains develop new neurons (yes our brains do develop new neurons and new neuronal connections). According to Panksepp SEEKING is the basis of addiction (we all know the term drug seeking). What psychology calls the reward system is a small part of the SEEKING network. The reward system is, in part, Medial Forebrain Bundle, but it is so much more than just reward (Panksepp, 2014). It is curiosity and enthusiasm. It impacts anger. Interestingly, there are different types of anger, one is related to the SEEKING system which is predatory rage and is considered pleasurable. Rage associated with SEEKING may also be primary to sexualized rage, part of the rage associated with sexual addiction and sexual perpetrators (sex addicts are not necessarily sexual perpetrators). Animals with predatory rage try to increase it, while those with agitated rage try to decrease the experience. It seems that both RAGE and SEEKING circuits would be involved in sexualized rage and may be dependent upon the individual’s life experiences and genetics.

Panksepp argues that the description of “reward systems” in the brain disregards much of the processes and role of affect in our behavior. In fact deep brain stimulation of the Medial Forebrain Bundle (the reward system) create “states of positive enthusiasm, that normally accompany the appetitive-foraging phase of behavior in our species, as we have long predicted” (Panksepp, 2014, p. 210). This suggests that much more is happening than a simple behavioral view of reward and punishment. It adds a level of understanding to why the rewards are so powerful. If it were as simple as the behaviorists suggest, quitting an addiction would be easy via extinction and other behavioral interventions. Unfortunately addiction are not so easy to stop. It is not simply pleasure but an enjoyable feeling state that is directly related to our survival instincts.

However, he recognizes secondary and tertiary emotional processes that work in a circuit (see chart). Secondary processes are learning processes that arise from various forms of conditioning (rewards and punishments); while the tertiary process is our thinking and ruminating and what is commonly associated with emotional life and that is impacted by interventions such as Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. Tertiary processes are the worrying over and over what will happen if, the catastrophizing in anxiety, and the thoughts about how one will get a fix in addiction (Panksepp, 2010a).

In Archeology of Mind (2012), Panksepp writes, “Most modern psychoanalytic and cognitive-behavioral approaches to therapy fail to see SEEKING as a basic emotional urge. Some researchers also tend to confuse FEAR and PANIC/GRIEF, seeing anxiety as a single manifestation” (p.xv). I would add that therapist and doctors too see anxiety as a singular expression, when often the nuances are quite distinct. It is important to determine the difference as interventions may be more or less effective depending on the system involved. For example, when PANIC is involved I often need other strategies than cognitive interventions. Since SEEKING is such an important factor in addiction, more will be written about this and other systems in later posts.

CARE (nurturance): CARE is as it sounds, it is our affection for those close to us and for the world around us. It is our need to feel cared for and to care for others. It too is primary to our bonding with those we love.

LUST (sexual excitement): LUST is also part of our love for others and our need for sexual intimacy. In terms of survival we must have sex to propagate the species. Clearly in sexual compulsivity LUST is a primary process, however, it may not be the first activated for many individual but become active after the FEAR or PANIC or another system is involved.

PLAY (social joy): PLAY is integral to our emotional life, all animals play. It is the basis of joy in the brain. PLAY is imperative to brain development and attachment. Research has shown that playing enhances frontal lobe development. Play therapists know that getting on the floor and playing with one’s child improves attachment, this is why. As adults we must continue to have social engagement and playfulness. This is often a difficult task for recovering addicts, in part because play seems confused by SEEKING (excitement) and fun becomes the use of the drug or behavior. In other words the excitement of fix feels like fun, although it is another brain circuit altogether. This is where our secondary and tertiary processes come into the mix. PLAY stems from brain areas that are more basic - not higher order thinking. This is in part why Panksepp believes the removal of play from schools has led to a spike in ADHD. Finally, play reduces aggression, suggesting the link between these systems.

As you can see these networks interrelate. There is a saying in neuroscience, what fires together, wires together. This means that neurons that fire at the same time become paired together. This is a completely unconscious process. You can see how this plays out in various forms of addiction. SEEKING if activated with LUST leads to sexual searching. If our PANIC circuit is triggered and was alleviated by the enjoyment of LUST (sex), and this happens frequently the two networks in the brain will then fire off simultaneously when even one is activated. Additionally, if CARE and LUST become paired, for example through sexual abuse or other secondary and tertiary processes, then sex and intimacy become confused in a basic, unconscious way. I asked Dr. Panksepp if this is possible and he explained yes it was, in this manner:

"The SEEKING System is truly enormous, and beside integrating appetitive eagerness (enthusiasm), it also can be devoted to LUST issues where gonadal hormone receptors are concentrated (POA), as well as CARE where oxytocin and prolactin receptors are concentrated. Thus, all the positive emotional system, including PLAY converge on the SEEKING urge, but are distinct enough to be seen as distinguishable appetitive urges" (personal communication, 2014).

When secondary process of rewards and punishments come into play and then our interpretation of events and what this means about who we are, patterns of coping become quite complex. Given this complexity, changing behavior becomes very difficult. Anyone who is in recovery from sexual compulsion can attest to the difficulty of staying on the path.

This is not to say that all is lost and that adults are not responsible for their behavior. They most certainly are, but what this suggests is that we have to be aware of and work with the primary circuits for change to occur. Those working with addictions know this and do this inherently. Programs try to develop healthy fun activities to reengage the PLAY circuit with new behaviors. They are trying to disconnect PLAY from SEEKING, specifically drug seeking, and build the important social connection all of us need. SEEKING then changes too. In essence part of the work is pairing PLAY with CARE. However, addictions can be cunning, powerful, and baffling- a trigger can arise at any time. The primacy of these circuits gives us an understanding of why.

Finally, what most people call positive feelings, “indicate that animals are returning to “comfort zones” that support survival, while negative affects reflect “discomfort zones” that indicate that animals are in situations that may impair survival” (Panksepp, 2010a; Panksepp 2010b). Despite Panksepp’s word choice, this model suggests, and as Linehan and many others explicitly point out, that emotions are not good or bad, negative or positive, but they are either what Katie O’Shea describes as life protecting (FEAR, RAGE, PANIC) or life enhancing, helping us regulate our nervous systems by calming us and returning us to homeostasis (SEEKING, CARE, etc) (2014, training). Thinking about your feelings in this way can helps you accept your emotional experiences, become mindful of the process, and therefore less reactive to a feeling. Judging your feelings as bad only leads to resistance and a desire for the unpleasantness to go away and fear that the pleasant emotions won’t last. When faced with a difficult feeling, remind yourself that this is how your brain is designed to respond in order to protect you. Asking, “What is this emotion trying to protect me from?” can help shift your perspective.

REFERENCES

Bradenbock, Being a Brain-Wise Therapist.

O’Shea, K. (2014). When There are No Words. Training.

Panksepp, J. (2014.) Integrating Bottom-up Internalist Views of Emotional Feelings with Top-down Externalist Views: Might Brain Affective Changes Constitute Reward and Punishment Effect within Animal Brains? Cortex; 59: 208-213.

Panksepp, J. October 27, 2014. Email communication

Panksepp, J. (2012). Archeology of Mind. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Panksepp, J. (2010a) Affective neuroscience of the emotional BrainMind: Evolutionalry perspectives and implications for understanding depression. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience; 12(4): 533-545.

Panksepp, J. Archeology of Mind P.xii

Panksepp, J. (2010b). Dialogues Clinical Neuroscience. 12(4):533-545. Affective Neuroscience of the Emotional BrainMind: Evolutionary Perspectives and Implications for Understainding Depression.

Weintraub, P. (2012, May 31) Discover Interview: Jaak Panksepp Pinned Down Humanity’s 7 Primal Emotions. Discover Magazine. http://discovermagazine.com/2012/may/11-jaak-panksepp-rat-tickler-found-humans-7-primal-emotions.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed